Exodus 1:8- 2:10

People are meaning makers. We all search for meaning in our lives and in the events that happen around us. We are also storytellers. All cultures have stories that they tell. We tell stories as a way of fostering social cooperation, empathy and justice, and teaching social norms. Storytelling is also a way constructing identity, constructing our understanding of who we are, both as individuals and as a society. Storytelling is therefore important as it helps us feel a sense of belonging to a culture or society.

Storytelling is also important as we tell stories of our history. We, and by “we” I mean humans as a collective, have short memories. Without stories being told what happens in one generation is lost to the next. A few years ago one of my kids asked “who is Princess Diana?” They were born after her death and with the story of her life and death they would not have known anything about her. Another example is Lindy Chamberlin. You may have seen the TV programs being advertised that again are going to tell her story and the story of the disappearance of Azaria. Again, my kids did not know the story, they had no idea what it was all about.

Having stories live on can be important. Each year we honour ANZAC day and remember those who fought in war not to celebrate war but to remember the horrors of war, lest we forget. Stories of WWII and the Holocaust which grew out of Nazi ideology bare repeating, lest we forget. Two weeks ago, the anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bombs in Japan was a time of telling stories. Stories that the survivors of the bombs do not want lost in the hope that we learn from our history and do not repeat it, lest we forget. The importance of remembering these stories is not just for those who experienced the event but all of humanity.

We need to keep telling our stories so our history and knowledge can be carried forward and not forgotten. We need to hear different stories of the same events. I have been both to Pearl Harbour and the Hiroshima and the stories told at those two places are quite different and both have truth. Losing our stories or only listening to one side of a story distorts the story and may be why humanity seems to keep repeating history. There is a long history of empires rising and falling, of conquering land, of taking power and fighting to keep it. It plays out in persecution and oppression of people and killing ethnic or national groups. Names, places, the weapons of choice and maybe even motivations change but basically it is the same thing happening over and over.

I know a few Christians who think that we do not need the Old Testament, the Hebrew Tanakh. It is true it is a story of the Jewish people, the Israelites, the Hebrews and the stories within in part are identity stories which we may not identify with. These are, however, Jesus’ stories. Stories that shaped Jesus’ identity. I think the stories of the Tanakh are important. Important as it helps us understand Jesus.

Important because they are sacred scriptures and help us understand God and God’s relationship with people. Important because although technology may have evolved in many ways people have stayed the same. To quote Shirley Bassey “It is all just a little bit of history repeating”

This week’s bible reading begins “Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.”

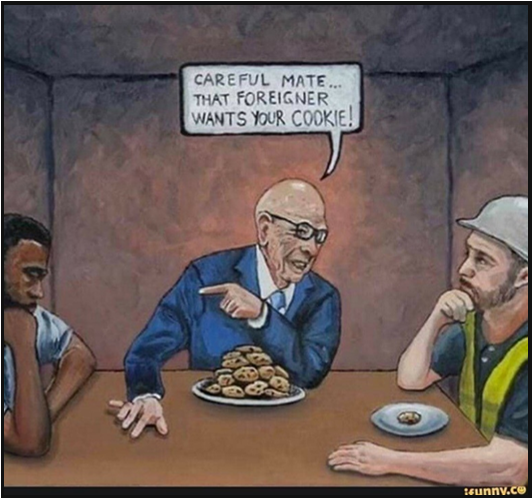

Remember Joseph entered Egypt an Israelite, a foreigner, but became a hero, getting them through those 7 years of drought. But now the Israelites are back to being foreigners. They are the “thems”. There is fear “they” will increase in number. Pharaoh is using the

age-old strategy of create an “enemy within” to stir up fear of the foreign or immigrant other. “Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, or they will increase and, in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land.”

Do you hear echoes of this in the modern Australian context? Fear of the Asian or Muslims taking over?

Pharaoh wanted to keep “them” in their place. Keep “them” under control. First this is done by oppressing them with forced labour making them build Egyptian cities. But still they increased in number so:

“The Egyptians became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labour. They were ruthless in all the tasks that they imposed on them.”

When still this did not work Pharaoh commanded the Hebrew midwives to kill any boys born at birth. The intention is that they be bred out by killing the males, a little bit of ethnic cleansing. Again, do you hear any echoes of this ancient story with our recent past?

Some may wonder how this works since the girls can live and will go on producing children. In a patriarchal society, particularly ancient patriarchal societies where women were seen as incubators of male seed, it is just the male line that matters. The females can live and produce babies of Egyptian men as those children would be considered Egyptian.

The Hebrew midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, may or may not be Hebrew. The grammatical construction in Hebrew is unclear as to whether “Hebrew” refers to the midwives’ ethnicity or that of the women they serve. Either way they do not fear Pharaoh, rather, they fear God, or better translated, they respect God and so they defy Pharaoh and refuse to follow the command to murder the Hebrew boys. An ancient example of civil disobedience and resistance. When faced with the failure, Pharaoh again ups the anti and commands his people that any infant Hebrew boy they find is to be thrown into the Nile.

With this hanging over their heads we hear the story of

2 Levites marrying, conceiving, and bearing a son. In the NRSV the baby is described as a “fine baby”. Read in its original language, Hebrew, we see the same language used to describe creation in Genesis 1, “And God saw that it was good.” So this verse (Ex. 2:2 ) could be translated, “The woman conceived and bore a son; and when she saw that he was good …” Something about this baby gives his mother, tragically unnamed, the courage to also act out in resistance of Pharaoh’s command. She hides him for 3 months before placing her child in a basket and on the river. The NRSV uses the word “basket” to translate the Hebrew word “tevat”. This word is also the word that in English is translated as “ark” in the Noah story. This baby boy is placed in a boat of salvation. These little references to creation and a new beginning after the flood are incorporated into this,

the story about the creation of the Israelites as a

people/nation no longer just a family or clan which unfolds throughout the entire book.

The baby’s sister stands at a distance, but you can imagine that her role is not just to passively watch but to help ensure he is discovered by the right person. This baby in his ark, his boat of salvation, floats down the river and is found by the daughter of Pharaoh “and she took pity on him”. The baby’s sister steps forward at just the right time and offers to “get you a nurse from the Hebrew women to nurse the child”. Did it cross this Egyptian princess’ mind that this wet nurse with her breasts full of milk was the baby’s mother? If so she does not threaten her or treat her harshly but pays her to look after the child. She does this until the child grew up and she then brought him to Pharaoh’s daughter who took him as her son and named him Moses, because, she drew him out of the water.

Rev Tammy Hollands