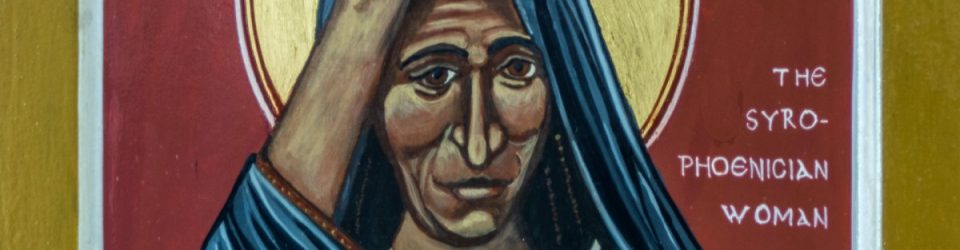

Mark 7:24-30

From there he set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there. Yet he could not escape notice, but a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. Now the woman was a Gentile, of Syrophoenician origin. She begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. He said to her, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” But she answered him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” Then he said to her, “For saying that, you may go—the demon has left your daughter.” So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone.

My siblings and were all raised as members of the Canberra City Uniting Church, and each of us were blessed to be not the only kid in our age groups; we all had a small group of comrades with us. My younger brother’s group however were more often in the worship service than out of it, at least for a few years, when there was a dearth of Sunday School teachers. And I remember once, on a Communion Sunday, presumably because they had nothing better to do, my little brother and his group of buddies made their way up into the sanctuary during a hymn, and crawled under the Communion table, making themselves a little cubby hole, totally oblivious to the fact that there was a church service going on. The congregation had no idea how to respond to this – until they realised that this group of children were, in their own way, participating in a rite of passage in relation to that sacred space. At Canberra City Uniting, children were discouraged from taking Communion until they had their service of Confirmation – not just to be cruel, but because it was felt that children would not understand the significance of Communion until they were older. This came to mind, as I prepared for this sermon on the reading we heard this morning. “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” My little brother and his friends didn’t have to contend with any hungry dogs for space or crumbs under the Communion table, but perhaps like the Syrophonecian woman, they were claiming their place at the Table of the Lord in the only way they knew how.

Admission to the Table has been a massive issue in the Church throughout its 2000 years of history. Many questions arise, like: what preparation does a person have to do before being accepted at the Table? What initiation rites must they first undergo? How old must someone be before being welcomed to the table? How much must they know and understand? And then of course, the removal of one’s right of access to the Table has been a major form of punishment in the church’s disciplinary procedures – a practise called Excommunication. It has usually been reserved for particularly serious sins, but there are lesser forms of “mild” excommunication too. You might remember the Rainbow Sash movement and the controversies they caused in the Catholic Church here in Australia in 2002, when gay Catholics presented themselves to receive communion from Archbishop Pell, wearing rainbow sashes to identify themselves as gay, thus challenging the Church’s condemnation of their sexuality. While they were not officially excommunicated, Archbishop Pell ruled that they could not be served communion from the Table while they were wearing the sashes because the wearing of them was an open defiance of the church’s teaching and thus ruled them out.

Now this question of the rights and wrongs of Table fellowship is not a new issue created by the Church. It is older than the Church and, in fact, most cultures have fairly clear expectations of who can break bread with whom. Sharing a meal has always been a powerful symbol of acceptance and belonging, and limitations of who one can eat with have always been powerful markers of boundaries between different people. So for the Jewish community in which Jesus belonged, the kosher food laws and the laws against eating with Gentile people were crucial components of their endeavours to maintain a distinctive Jewish identity in their pluralistic Greco-Roman world. We Christians inherited that history and continued to understand the Table as an important place for defining who we are, and how we are distinct and different from others. And of course, once you define yourself in that way, it is only a very short step to seeing yourself as superior to others and as belonging to God’s favourites, and to seeing others as inferior and rejected by God and therefore to be shunned and avoided by us.

It is into just such a set of understandings that the Syrophonecian woman in today’s story speaks. She has come to Jesus, not seeking a meal, but seeking help to heal her daughter. But because sharing food is such a major symbol of the boundaries that separated her as a Gentile woman from him as a Jewish man, food quickly becomes the metaphor for the negotiation of their relationship. “Let the children be fed first,” says Jesus, “for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” Yikes. It sounds shockingly offensive to our ears, but it probably wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow at the time. The understanding was that the gifts of God are for the chosen people of God, and those gifts were dishonoured if they were shared with those who are “not worthy”, the outsiders, the excluded, the excommunicated.

I wonder what was going on for Jesus when he said this shocking insult to the woman. Was he having a bad day and a mindless moment, and thoughtlessly repeated a common saying? Maybe. Was he reflecting the racist assumptions he had grown up with? Unfortunately it is possible; there is no doubt Jesus would have been raised to give thanks to God every day that he was born a Jew and not a Gentile. Or, was he simply testing her? It is impossible to be sure, but I don’t want to dwell on the question; I’d like to go in a different direction.

The Syrophonecian woman answered him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” In that culture, the woman has taken a huge risk here. She is a Gentile (problem) woman (problem) facing a Jewish male rabbi, and she dares to speak back to him, taking his own words and turning them back on him, as she persists in calling him to do something he has already refused to do for her. And what she is doing with her daring backchat is suggesting that God’s table is not really so closed, but that people like her, people long excluded, have not the privilege, but the right to come to it and expect to be able to receive, and eat, and be satisfied.

And Jesus says to her, “Right you are. And for saying that, what you were looking for has been given to you. Go home and you will find that your daughter is well.”

We are understandably shocked at Jesus calling the woman a dog… sounds pretty racist to me… but in his day, the big shock in the story would have been that this male Jewish rabbi would concede an argument to a presumptuous Gentile woman, and that he would not only concede it, but commend her for it. There are probably a number of implications we could draw from that, but let me just pick out one. Jesus is recognising, and so calling us as his followers to recognise, that we have much to learn from those who know the experience of being excluded from our in-crowd. It is crucial to our understanding of Jesus that we see how fully he entered into the experience of the excommunicated, the outcasts, the different-to-us.

And so for us in the churches, we will be sure to miss the point, if we argue and debate about the place of LGBTIQ people at the Table of God’s love without opening ourselves to real conversation with LGBTIQ people and listening to the insights born of their experience of our exclusions and hostilities. Similarly, if we want to discuss reconciliation for Indigenous peoples, we’d better not come with a colonialist mindset again and try to impose it; we’ll need to listen and seek to understand from their experience. If we want to explore questions of our relationship to peoples of other faiths, we’ll be talking in ignorant circles if we don’t make friends with some Muslim or Hindu neighbours and listen and learn what it is like to be “other” in a country where being people of faith is normally assumed to mean Christian. I could go on: asylum seekers, women, young people, people with mental illnesses or physical disabilities, whoever. Jesus invites us to join him in allowing ourselves to be taught by those whose experience has been of exclusion by the powerful.

This is really hard, for everyone. This is partly because hearing the realities of the oppressed as true is particularly difficult for those of privilege – to accept a foreign reality without demanding qualifications, to stop talking and listen without interrupting, to hear without working their experiences into the dominant narratives within us. And it is partly because we all grow up shaped by the values and assumptions of the world around us. We are not responsible for the influences to which we are exposed in our vulnerable formative years.

I was educated at the Canberra Girls Grammar School, the richest school in Canberra – I went on a music scholarship, but even so, as a student at that school, I soaked up the idea that my peers and I were superior to other people because we had been there. We couldn’t help it. It was in every school song. It was in every principal’s address. It never occurred to us to question it because we were never exposed to an alternative view. It was only after I left and moved to Sydney, that I was confronted with the possibility that people who lacked the comforts and education and abilities that I had were created in the image of God too, and deserved to be treated as my equals. I was confronted with the truth of my own brokenness and incompleteness, as a minority in some ways, but as part of the elite in so many others. I was confronted by my own knee-jerk responses to the dogs of our world, thus perpetuating oppression. At that point I had to make a choice. At that moment I became responsible for my attitude. From that time on I have had to choose, and continue to choose whether I will be an elitist or not. Maybe, so do you.

As we continue to choose our choices, perhaps we will begin to more fully and deeply understand what this woman asserted and what Jesus’s subsequent response confirmed: that this Lord’s Table, the cosmic banqueting table of God’s love and mercy, is more radically open than we could ever imagine. It is so radically open that it will continue to shock us and bewilder us. It is so radically open that almost any time we think we should be policing the boundaries and keeping someone away, we will almost certainly be wrong.

Another piece of good news is that the scandalously open Table of the Lord is an enormous comfort, whenever we have felt that we might deserve exclusion ourselves, for whatever reason. God invites us, deserving or not, and welcomes us to feast on the bread of compassion and drink from the cup of grace. But it other times it is just as much of a confronting and uncomfortable challenge, because God’s reckless generosity extends to people we don’t like and don’t trust, to people who offend us and seem to us beyond the pale and beyond hope. And I suspect that the only way to miss out on a place at God’s Table is to refuse to be seated with the unworthy others at the Table. Of course, if we think we are worthy, we are probably deluding ourselves, and our right to be at the Table is no less a gift of far-reaching grace than theirs.

Our NCLS and Life and Witness consultation data tells us that the number one strength at West Epping is hospitality. So my prayer for us this morning is that West Epping grows in its strength of hospitality, and radical hospitality at that – seeking to be a place where all people are welcome at this table, even and particularly the children. For what God wants to feed them on is not just the crumbs that fall from what is given to others. God offers to them and to all of us, the deserving and the underserving, the understanding and the ignorant, young and old, straight and gay, local and foreigner; to all of us God offers and welcomes us to the full banquet of love and mercy and reconciliation and life. Come out from under the Table and feast! Amen.